Every so often you get an idea in your head that needs to be visualized– a character that yearns to leap from the page, or a logo to express what your organization is about.

If you’ve never commissioned art before, or you’ve had trouble doing so in the past, you may be confused on how to give an artist what they need to bring out the best version of your idea they can.

NOTE: This guide works great in conjunction with our other guide, 7 Tips for Getting the Most out of the Convention Commissioning Process.

You should check it out if you’re going to a con!

If This is your First Time

Art is how we communicate ideas and emotions through media.

If an idea is best expressed through a visual medium, for example, then this leaves you with a chicken and egg problem:

how to show the artist what you want without already having the piece done!

If you’re having a character drawn for the first time, the best thing to have is a description.

Writing a Good Description

They say ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’, however you can usually get away with far fewer.

When writing a description for an artist to reference, you do not have to be the most eloquent prose writer– you just need to communicate the physical attributes of the subject and what you want them doing or wearing.

Method One: Roleplay Description

One character I’ve made is a fennec fox named ‘Zorro’.

As part of my records about him, I keep a description for art or role play, which you can see here:

This less than towering creature, five foot four inches tall (if youinclude the ears), has a markedly expressive face that makes him quite memorable.

Tawny colored fur ruffles in the wind, and brown eyes scan about.

His twitching nose always seems to be finding some sort of scent, or perhaps his eyes are just wandering and surveying the beauty of life.

He wears a nice sort of school uniform– though it seems quite worn, a thread here and there sproinging off like an unruly child rebelling from its mother textile.

His bare plantigrade footpaws leave little dents in sandy soil, but are otherwise silent when he scurries around. His voice, however, seems surprisingly flexible, as do his expressions.

Generally he seems quite happy, and he carries with him a bag that has a few fountain pens and several sheets of paper.

Some of them are poking out, little scribblings shown on them.

The above description is enough for an artist to work with, though it has some limitations.

The biggest limitation is that it’s hard to see, at a glance, all of the details.

The reader must go through the entire paragraph and hope to catch everything.

Below is the resulting sketch I got back from Michelle Light:

Take a look at the description and compare it with the result.

As far as the character goes, I’d say this piece does an excellent job of portraying Zorro. However, there are a few things to note:

1. Details which weren’t mentioned were filled in:

The description I gave does not go into detail on Zorro’s fur patterns, other than mentioning his general tawny color.

Likewise, no real detail was provided about Zorro’s bag or school uniform style.

This means Michelle had to come up with something and infer what might be best.

Anything you do not describe is up to the artist to interpret.

2. The art style and medium meant some loss of detail:

Zorro’s fur color is brown.

As this is a sketch, he could be blue for all we know.

Additionally, the description gives an account of the texture of his uniform, mentioning a lightly worn appearance.

Michelle’s art style, which is a smooth, toony look, would have a harder time conveying this than a more realistic style.

3. Something was missed, but that’s OK:

One of the details in the description mentions that Zorro has ‘fountain pens’.

Zorro was written for a steampunk environment, and so this technology is what would have been prevalent.

In the picture, we see a pencil and a capped modern pen (possibly a permanent marker).

Small details like this may not stick as well when the artist is reading a description– they’re human like everyone else and make mistakes!

However, when I got the piece back, I should have examined it more closely, given feedback and asked for her to adjust it.

I did not do this, and I’m sure Michelle would have corrected it if I had brought it up.

Method 2: Bulleted List

An artist usually doesn’t need to know, in too much detail, about the character’s background to draw them–in fact, too much additional detail can be very distracting!

For example, take this excerpt from the role play description:

His voice, however, seems surprisingly flexible, as do his expressions.

An artist cannot easily draw how a voice sounds, so this information isn’t very helpful.

A more succinct, less ambiguous way to describe your character is with a bulleted list. Here’s the same character, described in this manner:

Zorro…

- Is 5’4 (if you include the ears)

- Is a fennec

- Is male

- Has a very expressive face

- Has tawny colored fur

- Has brown eyes

- Has a small frame

- Wears a nice school uniform, though it’s a bit worn with the odd thread here and there

- Doesn’t wear shoes or anything on his feet.

- Is plantigrade, not digitigrade

- Carries a bag, specifically with fountain pens and papers with scribblings

- Lives in a steampunk world

Please draw Zorro looking over a piece of paper he’s written on.

This bulleted list is much easier for an artist to track, and makes it more likely that no important details will be missed.

The last listed item, referring to the character’s environment and background, will help the artist with any judgement calls for things such as backgrounds.

The final line, not in the list, describes what we want the character doing.

This method does not guarantee the artist won’t miss something, or that you won’t have notes for them, but it should make miscommunication less likely, and less severe.

Don’t Forget!

Here are some things you’ll want to include in a description for an artist:

- Height

- Build (petite, skinny, average, lean, swole, etc)

- Species

- Coloration, hair/fur/skin details and patterns

- Sex

- Demeanor, eyes and expression

- Clothing, tattoos, or piercings as applicable

- Any other unique attributes of their physiology (Extra long tail? Additional or fewer fingers? Scars?)

- The pose you want the character in, or what you would like them doing.

Reference Images

If your character has a detailed feature, such as a tattoo or a sword or some other outfit, it can help to provide to the artist a reference to work from.

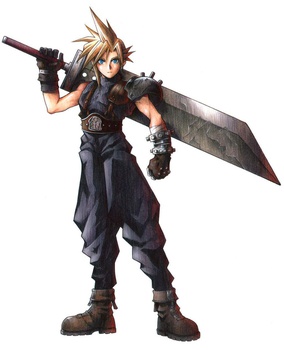

I once had a character with an oversized sword, and wanted that sword to look similar to (but distinct from) the sword wielded by the character Cloud Strife in Final Fantasy VII.

To convey this, I found a reference image. Here’s one from the game’s concept art by Tetsuya Nomura:

Here was the resulting piece by Dark Natasha:

Having that reference made describing the proportions of the sword much easier.

You’ll note the sword is not exactly the same, either, though it is reminiscent of the source.

Reference Sheets

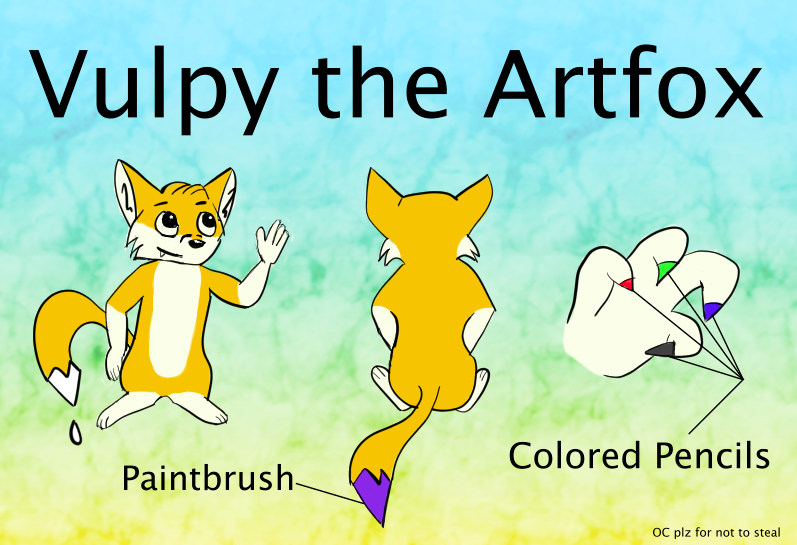

If you’re planning to get many pieces done of a character, especially from more the one artist, you’ll want to get a reference sheet.

A reference sheet is a standard method of showing off the physical appearance of your character (and sometimes includes tidbits about them on the side).

It typically contains nude portrayals of the character as well as clothed versions.

Much like a character description, a reference sheet does not have to be the highest quality to serve its purpose.

Its purpose is to make sure that you and the artist are on the same page about how the character looks.

Some artists insist on having a reference sheet for characters to reduce the chance of miscommunication or hurt feelings.

I’m not ready to sell art of my own, but I am able to do enough drawing to make a basic reference sheet or ‘refsheet’.

Here’s the one I made for Artconomy’s mascot, Vulpy the ArtFox.

Here’s some of the art that I commissioned using this refsheet:

By Betsy the Beaver

By Halcyon

Halcyon was able to find something I’d forgotten on my refsheet– pawpads!

We had to discuss what color the pads would be and settled on pink.

Remember: Refsheets are there to help you get started.

You can always commission a new one based on the previous one.

Budget and Deadline

Determining whether an artist fits your budget is important.

Many artists have a pricing sheet available and linked on the profiles of the sites they post on.

If they’re using Artconomy, pricing will be listed right on their profile page under their products.

However, some artists don’t have their prices listed, or you may not know where the prices are.

Telling them up front what your budget is makes it easier for them to determine if they are able to accommodate your requests and to what level.

Make sure to get a price from the artist before beginning so there is no confusion on payment.

In fact, you’ll want to seek to eliminate as much ambiguity as you can when ordering, to stay safe.

You should also tell them if you have a deadline, and when that deadline is, upfront.

Some artists may have several orders they’re working on and won’t be able to make your deadline, in which case you’re better off looking for another one.

Do not expect an artist to respect a deadline they have not been told– and don’t tell them after payment has been sent, but before.

This will prevent you from running into any unexpected problems down the line.

Putting it all Together

Artists like it when you’re prepared with everything they’ll need ahead of time.

When possible, I keep copies of my character reference sheets, and typed out descriptions of what I’d like drawn when going to conventions.

Then all I have to do is hand each artist a packet containing everything they need.

They read it over, give me a price, and then get right to work.

If you’re sending an artist a private message, make sure to type out everything you can in the first message. Do not lead with ‘Hi!’ or a similar one-line greeting.

This is wasteful of the artist’s time and doesn’t tell them that you are looking for a commission (which will call their attention to you) or what you want (which will help them get an answer to you faster).

If you have trouble getting all of your descriptions and references organized, or would just like a good place to catalog your characters, might I suggest checking out Artconomy?

We make it easy for you to find artists and keep a virtual reference sheet and portfolio for your characters!